Using thematic analysis in psychology

This is a summary of the first part of the journal article. In this section, Braun and Clarke define thematic analysis. In the next part, they outline a guide for carrying out thematic analysis.

Braun and Clarke present thematic analysis (TA) as a method all researchers should learn to develop core skills; while some consider it a tool, they see it as a method in its own right.

Its theoretical freedom means it can be used regardless of epistemological or ontological positions, or analytic methods.

The paper aims to define but not constrict TA as one of its best features is its adaptability.

Source: https://goo.gl/d7VCbW

Terms:

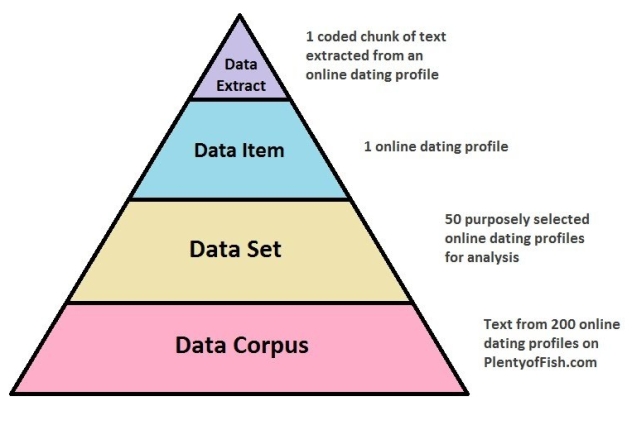

- Data corpus – all data collected

- Data set – data used for particular analysis, drawn from across corpus

- Data item – each individual piece of data

- Data extract – individually-coded chunk of data

What is Thematic Analysis?

It’s a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns – themes – which minimally organises but richly describes data, and often goes further into interpretation.

As it hasn’t been ‘branded’ like other methods, it is often not even acknowledged as method used, as it’s either named as something else or not named at all e.g. ““…data were subjected to qualitative analysis for commonly recurring themes.” (Braun and Wilkins 2003:30)” (Braun and Clarke 2006:80)

If attitudes, analysis, assumptions aren’t stated, it’s difficult to evaluate research.

Talk of themes as ‘emerging’ ignores role of researcher as interpreter / ‘noticer’, as if the texts themselves contained themes just waiting to break out at the notice of an objective watcher.

All reporting of research involves selection and rejection of data, so what is essential is theoretical frameworks / methods match researcher’s aim and that these are acknowledged as decisions.

Unlike (e.g.) Discourse Analysis (DA) and Grounded Theory (GT), TA is not tied to any theory; nor does it require to full analysis of GT.

Thematic DA covers a range of approaches including:

- Patterns identified as socially-produced but not discursively-analysed – SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIONIST EPISTEMOLOGY

- Interpretative form of DA

- Themes identified where language is made up of meaning and meanings are assigned socially – THEMATIC DECONSTRUCTION ANALYSIS

Thematic DA therefore overlaps with TA as they both look for themes across rather than within data sets, unlike narrative analysis or individual interviews, and it’s more accessible to new researchers as doesn’t require extensive theoretical knowledge of approaches (such as DA / GT).

TA can be essentialist or realist, constructionist or contextualist but theoretical position of analysis should be completely transparent.

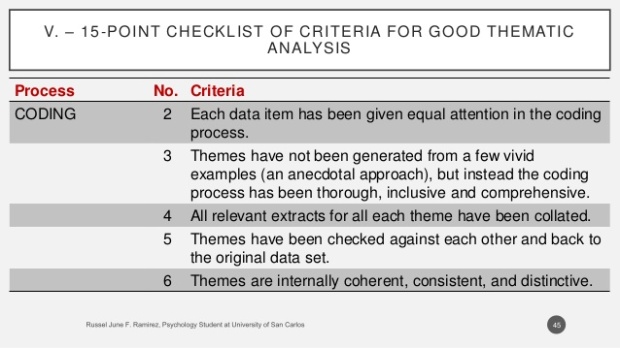

Decisions

Certain questions are never answered in TA papers, but should be. (See below.)

What counts as a theme?

This can’t be quantified definitively in terms of number of occurences or length, so we have to remain flexible and use researcher judgement.

A theme’s importance is not judged on prevalence but “in relation to overall research question” (Braun and Clarke 2006:82) so what matters is actually consistency in how you identify themes (or even prevalence).

Perhaps there’s a need for more debate around conventions of prevalence including why it might be important.

Rich description v detailed account?

Researcher must decide the type of analysis and what s/he wants to show e.g. a rich thematic description will show predominant themes across whole data set, but will lose depth – perhaps useful approach for discovery in areas where not much research has been done.

Alternatively, researchers can go deeper – within or across data sets – into one or more themes related to a particular aspect or question.

Inductive v theoretical TA

Researchers can use inductive (bottom up) approach whereby themes coming out will be unpredictable and data will be coded without pre-existing coding framework – very data driven and similar to GT – although of course cannot be entirely epistemologically ‘pure’ because of the role of the researcher.

Another way is to drive the research by a theory or analytic interest in the area, and code for a specific research question (which will produce less rich description overall).

Deciding how and why you are coding the data is needed to choose between inductive or theoretical approach.

So, for example, a researcher could look at the data and see any patterns related to a broader topic (see what comes out of the data – broad agenda), or could look specifically for themes related to a particular aspect (go in with a narrower agenda).

Source: https://www.slideshare.net/russeljuneramirez/a-summary-on-using-thematic-analysis-in-psychology-71940024

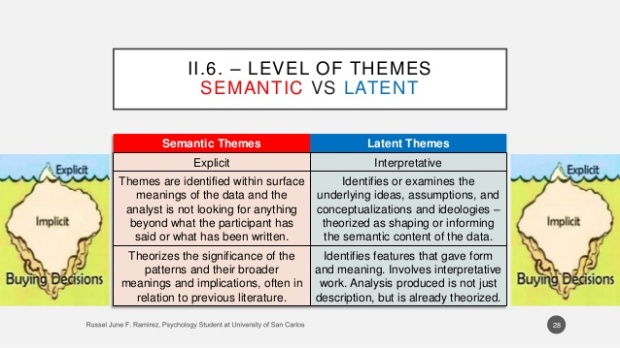

Semantic v latent themes

TA typically uses one or the other.

With semantic approach the focus is on surface / explicit meaning which is described and then interpreted in terms of the significance of the patterns, usually related to previous research (e.g. Firth and Gleeson 2004).

A latent approach looks beyond surface meaning to underlying ideas, concepts, assumptions and ideologies, so developing the themes themselves requires interpretation, meaning resulting analysis is “already theorised” (Braun and Clarke 2006:84).

The latent approach is commonly constructionist and so overlaps with thematic DA which increasingly also employs psychoanalytic interpretations (so that’s something TA could do too).

TA Epistemology: essentialist / realist v constructionist

“Epistemology guides what you can say about the data.” (ibid:85)

Essentialist / realist approach – theorise motivations, experience and meaning because language reflects and enables us to articulate meaning and experience (in a direct relationship).

Constructionist approach – perspective, meaning and experience are socially-produced (not within the individual) so the researcher will theorise sociocultural contexts and structural conditions that enable accounts. Latent analysis tends to be more constructionist and overlap with thematic DA.

Questions within qualitative research

- Overall research question (can be broad or narrow)

- Interview questions to participants

- Questions to guide coding

No necessary relationship between these types of questions; often better if unrelated. Some worst examples of TA analysis equate questions for participants as ‘themes’.

In summary, TA looks across data sets to find repeated patterns of meaning; form and product of TA varies but it’s important that final paper explains what was done and why.

NB

- The concepts latent, specific aspects, and constructionist tend to cluster together.

- The concepts semantic, across whole data set and realist tend to cluster together.

References

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006, 01). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Frith, Hannah & Gleeson, Kate. (2004). Clothing and Embodiment: Men Managing Body Image and Appearance. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 5. 10.1037/1524-9220.5.1.40.

Ramirez, R. J. (2017, February 09). A Summary on “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology”. Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/russeljuneramirez/a-summary-on-using-thematic-analysis-in-psychology-71940024

Further Resources

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2017, December 09). Thematic analysis – an introduction Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4voVhTiVydc

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2017, December 09). What is thematic analysis? Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4voVhTiVydc